McGill University student finds megalodons used to live in Canada

Posted February 11, 2025 1:14 pm.

Last Updated February 11, 2025 5:38 pm.

A McGill student’s fascination with the megalodon — a giant shark that used to live during the time of the dinosaurs — has lead to the discovery that the mighty beast might have once lived near Canada.

“I was obviously quite excited, very happy,” said Louis-Philippe Bateman, Megalodon discoverer and graduate student at McGill University. “This is the first time that Megalodon Fossils are officially described from Canada. So that was pretty exciting as a Canadian.”

A book Bateman once read described “giant, mysterious fossilized shark teeth discovered in the 1960s by fishermen dredging for scallops off Canada’s Atlantic coast.” This sparked his curiosity, which later led him down the path of paleontology as an undergraduate at McGill University.

It was through the undergraduate that Bateman dove into the study of the fossilized teeth discovered decades earlier.

“I’d read about these teeth when I was in high school, and it always stuck with me,” said Bateman, now a graduate student in the Department of Biology. “When I started working with Hans, I asked if we could take a closer look while we were at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa, where the fossils are held, for another project. That’s where this all began.

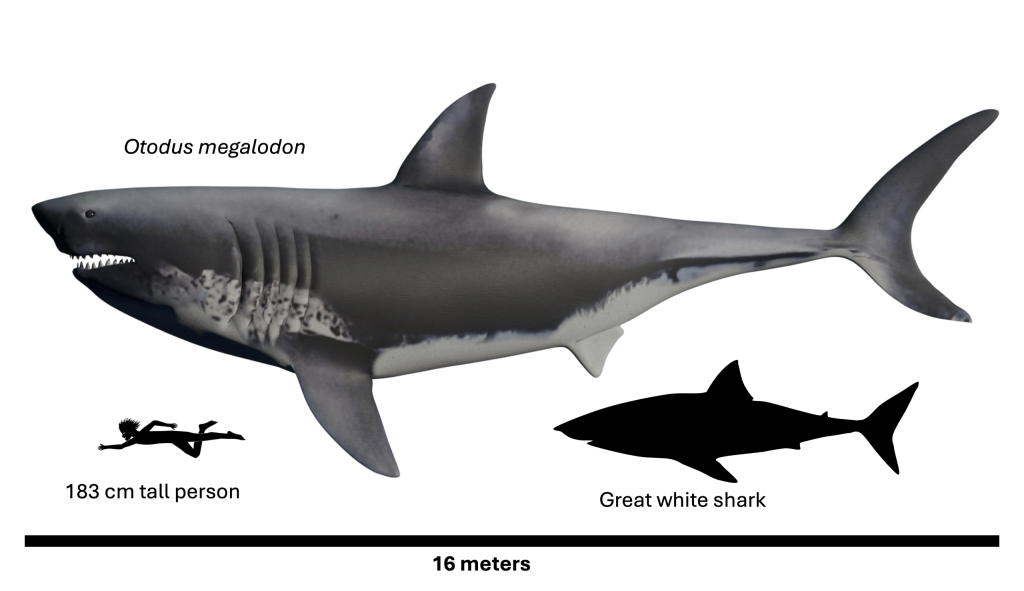

“Megalodon was likely the largest hyper-predator to ever exist in the oceans,” Bateman said. “Knowing more about its physiology and distribution helps us understand its role in ancient ecosystems and can inform future studies on marine biodiversity and predator-prey dynamics.”

Through his studies, he was able to identify that the fossilized teeth belonged to an Otodus megalodon — the largest shark species ever to exist.

The discovery also determined that the megalodon once existed in Canada.

“I think, to be honest, it’s a bit anti-climatic, to me, it feels like a regular scientific discovery,” said Bateman. “I know the general public is quite excited about it because probably it is, after all, the largest predator to have ever existed. But to me, it just feels like normally contributing to the body of scientific knowledge that we’ve been accumulating for hundreds of years.”

However, Bateman says the discovery wasn’t the easiest thing to do. Trying to identify the fossils required detective work and scientific rigour.

Some of the teeth were in museum collections, some existed only in historical fisheries journals or as photographs sent by museum curators, while others belonged to private collectors, some of whom were reluctant to share.

“About 90 per cent of fossils in collections remain undescribed,” Bateman said. “Eastern Canada, in particular, is underexplored compared to regions like Alberta. There’s so much potential for discovery.”

Despite this, Bateman was eventually able to find similar characteristics in the teeth, which led to the confirmation.

“Megalodon teeth are pretty distinctive,” Bateman said. “Once you find specific characteristics or combinations of them, you can confidently classify the species.”

Bateman says eight teeth were analyzed at the Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa –many coming from scallop dredgers in Georgia’s bank Nova Scotia.

Bateman’s study also looked at how the ancient climate influenced where the species was found.

It is believed that “temperature played a significant role in limiting megalodon’s habitat, aligning with what scientists know about its physiology as a mesothermic (partially warm-blooded) predator.”

Under the mentorship of McGill University Professor and Canada research chair in Vertebrate Palaeontology, Hans Larsson, Bateman says he’s been fascinated with fossils since he was a child.

“I think he was just fascinated that there could be these giant sharks living in Canada at the time,” said Larsson. “It’s very exciting because now Canada has megalodon. And also that it’s really like pushing the northern limits of where these animals could have lived in. If they were living there, right, and living in that thermal tolerance and the size of these animals, what the hell were they eating? And I think it just opens up many, many more questions.”

Bateman says Montrealers can breathe a collective sigh of relief that these animals are no longer present in waters.

“Well, it’s definitely extinct. I know there have been a couple of discovery channel documentaries that have come out seeking the megalodon in oceans around the world, but we have very good fossil evidence that it’s been gone for at the very least 500,000 years, if not about 2.5 million years,” said Bateman.

The two say this opportunity opens many doors in migration and research – bringing them one step closer in understanding the prehistoric past.

“I know this discovery definitely drives me on and motivates me to continue doing research, especially on Eastern Canadian fossils, because it turns out that even though our fossil record is fairly well known, it hasn’t really been worked on in the past 100 or 200 years to the same extent that it used to be,” said Bateman.

“I think a lot of people say to follow your dreams. And I think to a certain extent that is good advice. I think when you have a goal in mind and it really is important for you, well, you should go ahead and try and accomplish it.”