Quebec announces more mental health services for homeless amid cohabitation issues

Posted September 16, 2024 1:47 pm.

Last Updated September 16, 2024 6:53 pm.

The CAQ wants to better support homeless people who suffer from mental illnesses by offering more housing.

Social Services Minister Lionel Carmant announced on Monday that the government will guarantee that more beds will be available for people who can benefit from adapted and continuous care for eight to 12 weeks. They’ll be followed by a psychiatrist and a multidisciplinary team.

Minister Carmant said that once the person’s condition has stabilized, residential support services will be offered so that they can move into housing and stay off the streets for good.

“We are entering a new phase of our plan to reverse the trend that Quebec has experienced in terms of homelessness in recent years. Our goal is to help people with more complex profiles, who have mental health problems, to benefit from treatment adapted to their situation in order to give them the best possible chance of getting off the streets for good,” he said.

According to a government press release, in 2022, more than half of homeless people in Quebec reported having a mental health problem and some have substance abuse issues and are often isolated, distrustful, and resistant to traditional services and still face many obstacles when trying to get help.

The government is pledging $4.2 million for this project. PRISM is a housing program that was developed in Montreal to address gaps in services for people who are homeless and suffering from serious mental illness. They primarily help people with psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, and comorbid substance use disorders.

PRISM projects are designed to serve between eight and 16 people, depending on the capacity of the accommodation resource. Data shows that between 63 per cent and 81 per cent of individuals are still housed one year after completing the program and their quality of life gets improved.

“It is something that we are extending today to Montreal, but that I hope to introduce elsewhere in Quebec eventually,” said Carmant.

The government said the goal is to get hundreds of homeless people off the streets each year.

‘Doesn’t deal with our immediate concerns’

This all comes amid security-related complaints, surrounding some Montreal shelters, including the supervised drug-inhalation site, Maison Benoît Labre, in the city’s St-Henri neighbourhood.

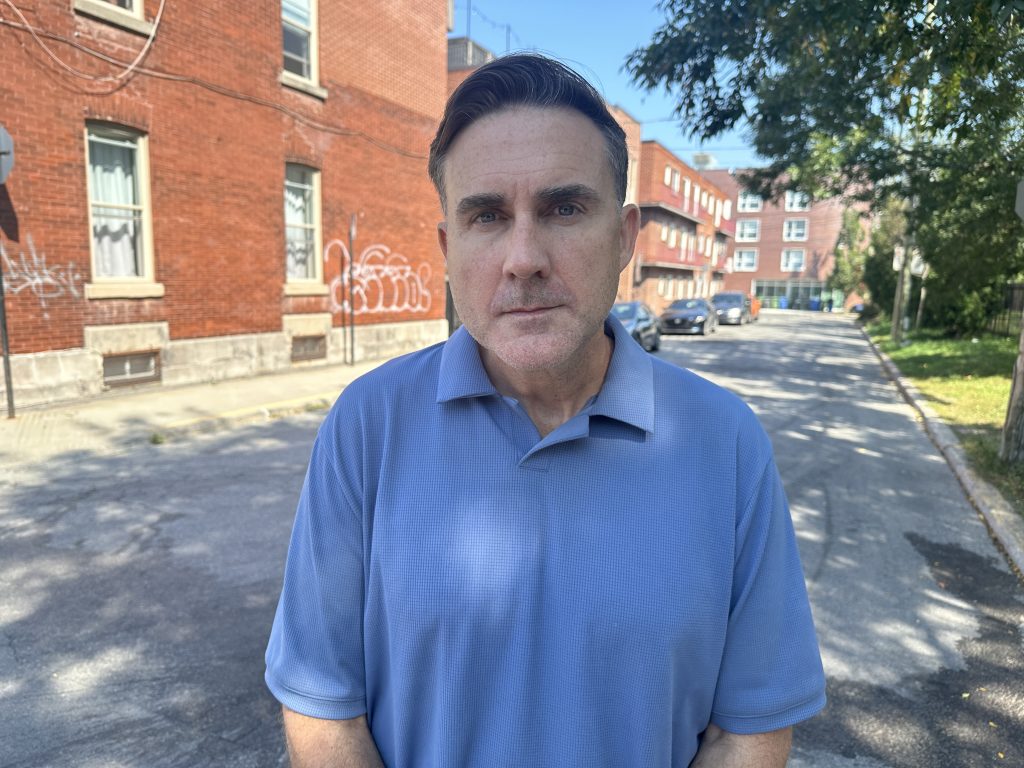

“What the minister has laid out this morning, I think is a really bold longer term vision,” said Michael MacKenzie, a professor in social work and pediatrics at McGill University, as well as a St-Henri resident, living near Maison Benoît Labre. “Working with local partners, […] I think that’s a welcome and wonderful thing, but that doesn’t deal with our immediate concerns.”

The ongoing controversy about the supervised drug-inhalation site is due to its location: less than 100 metres away from an elementary school.

On Monday afternoon, a man could be seen trying to force his way into the school yard, seeking to jump the fence just before children were coming outside.

Last week, a woman in her 20s was stabbed steps away from the site.

MacKenzie says there have been a number of aggressive and violent incidents in a short span, only weeks since the start of the new school year.

“Wednesday during the school lunch break, there was a violent conflict between a man and a woman on the lawn outside the center right next to the playground,” he said. “Thursday, the principal of the school had to send a letter home to parents highlighting that during the recess there was a person who had a moment of significant distress at the fence of the playground which children were witnessing.”

Last month, the City of Montreal announced it wanted to relocate the day services of the shelter, with Welcome Hall Mission stepping up to offer 100 meals free meals to redirect some of the people in the area.

Mackenzie, though, wants to see more done.

“It’s not to say that people don’t have a right to housing, it’s not to say that people don’t have a right to adequate mental health care and addiction support, which as a society we’re woefully failing on,” he said. “But our solutions aren’t all equal and this solution is not working and we’re not seeing evidence of a pivot that the minister promised us.”