Quebec cuts permanent immigration targets to 45,000 per year between 2026 and 2029

Posted November 6, 2025 10:46 am.

Last Updated November 6, 2025 11:58 pm.

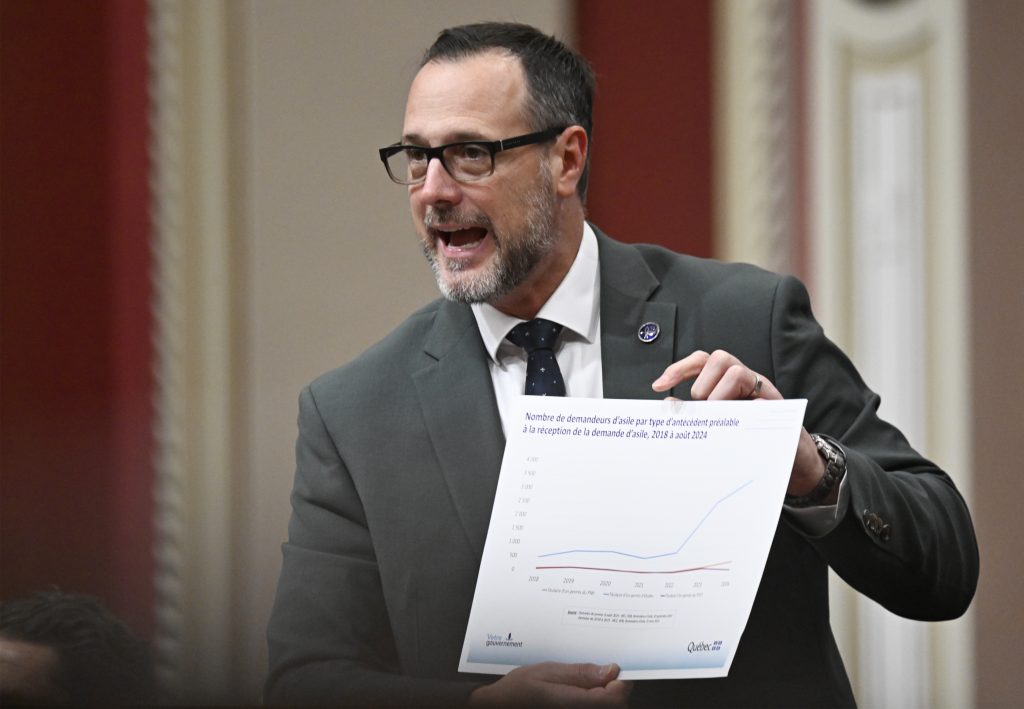

The Legault government is officially scaling back Quebec’s immigration targets, setting a new cap of 45,000 permanent residents per year from 2026 to 2029, a roughly 25 per cent reduction compared to the province’s current levels.

Immigration Minister Jean-François Roberge made the announcement Thursday morning, calling the adjustment an “obvious” one to protect the French language and ensure newcomers meet Quebec’s economic needs.

“Becoming a permanent resident, becoming a Quebecer, is a privilege,” Roberge said.

The new ceiling marks a drop from about 61,000 permanent residents expected in 2025. Roberge said the government is leaving itself some leeway, forecasting between 43,000 and 47,000 admissions depending on federal immigration changes.

Raising French requirements and changing who gets to stay

According to Roberge, the objective of the province’s new plan is to better select immigrants based on what he called Quebec’s economic needs, while at the same time cutting down on the total volume of the province’s newcomers, which he said currently acts as a weight on public services.

“The presence of such a large number of these people in the province is obviously not responsible for all the challenges facing Quebec, but it does place unreasonable pressure on schools, hospitals,” he said.

While he’s cutting the total number of temporary foreign workers, Roberge said his ministry wants more newcomers who are already living in Quebec to become permanent residents, setting targets for 54 per cent in 2026 and 65 per cent by 2029.

This comes a month after restaurants across Quebec complained that they risk shutting their doors if their low-wage temporary foreign workers could not secure feasible avenues to stay long-term in the province.

Roberge also plans to tighten French-language requirements. By 2029, 77 per cent of newcomers are expected to have at least intermediate fluency, up from the already recorded 50 per cent in 2018–2019.

New rules will also apply to temporary immigrants, who must now attain a level 4 on the province’s fluency scale if they plan to stay in Quebec for more than three years.

The government is aiming for a 13 per cent cut in the number of temporary residents by 2029, Roberge said, mostly in Montreal and Laval. According to Statistics Canada, about 562,000 temporary immigrants currently live in Quebec.

Roberge told reporters that applying a French requirement on temporary foreign workers was a “matter of respect for the Quebec nation” as well as a guarantee of security for the French language.

“If they want to stay here for more than three years, it’s a lot. It’s a huge commitment to Quebec,” Roberge told reporters Thursday. “If they love it here — fine. But they have to learn French.”

But some immigration advocates warn that cutting immigration while raising language expectations could make integration harder, especially after the province capped funding for French-language courses in 2024.

“They’re going to be working 14, 16 hours per day, six days per week,” said Carlos Rojas of Conseil Migrant, non-profit organization based in Montreal. “The alternatives to learn French are not there.”

He’s urging the government to solidly invest in incentives that would attract newcomers to the prospect of learning French, like paid classes and enjoyable places to study.

Rojas also believes that immigrants are being used as a scapegoat for issues relating to the housing crisis, Quebec’s healthcare system, overburdened schools and rising cost of living.

“The big problem here is that if they continue to treat the immigrants as a scapegoat, they will not be taking care of the problems, the real problems. And that’s going to make it really complicated for next year’s elections,” he said.

End of Quebec Experience Program (PEQ)

The government is also phasing out the Quebec Experience Program (PEQ) — a popular fast-track route to permanent residency for foreign graduates and temporary workers — by November 19, 2025. Applications submitted before that date will still be processed.

Once the PEQ ends, Quebec’s Skilled Worker Selection Program (SWSP), a points-based system prioritizing work experience and French proficiency, will become the sole pathway to permanent residency for skilled workers.

Candidates under the SWSP must first submit a declaration of interest before being sent to a pool of applicants from which the government may invite them to apply for permanent residence by sending a Quebec Selection Certificate (CSQ).

After receiving a CSQ, applicants can then apply to the federal government for permanent residence. French proficiency is a mandatory requirement.

Immigration lawyer Viviane Albuquerque says that eliminating the PEQ as an immigration avenue makes the process more uncertain for applicants.

“Now you put your profile in a pool of candidates,” she explained. “The government assesses your profile and compares it with thousands of others. Based on the needs of Quebec, the government can then make an invitation.”

Limiting applications to the SWSP also puts the ball in the government’s court in terms of choosing who gets to stay, Albuquerque added, since CSQs are only handed out to candidates who possess a sufficient number of points and satisfy the economic and linguistic needs of the province.

“With the program that we have now (…) we don’t know if the government is going to be inviting individuals based on (their) profession, based on your level of skills,” she said.

But with the SWSP as the sole avenue for permanent residence for skilled workers, Albuquerque said applicants can expect invitations from the government to be more predictable and frequent.

“Obviously the requirement to be able to speak French is now heavier for people across the board,” she said.

—With files from La Presse Canadienne